A couple of interesting challenges I solved in HTB CTF.

HM74

Category: Hardware/Medium: (325 points)

Description

As you venture further into the depths of the tomb, your communication with your team becomes increasingly disrupted by noise. Despite their attempts to encode the data packets, the errors persist and prove to be a formidable obstacle. Fortunately, you have the exact Verilog module used in both ends of the communication. Will you be able to discover a solution to overcome the communication disruptions and proceed with your mission?

Files

The following Verilog file was included. Examining the file indicates that this is an implementation of a Hamming (7,4) code. This method uses 3 parity bits for every 4 bits of data. This allows the receiver of the information to correct upto 1 bit of data errors (bit flipped from 1 to 0 or the other way around). If there are more than 1 bit errors, this parity is insufficient.

module encoder(

input [3:0] data_in,

output [6:0] ham_out

);

wire p0, p1, p2;

assign p0 = data_in[3] ^ data_in[2] ^ data_in[0];

assign p1 = data_in[3] ^ data_in[1] ^ data_in[0];

assign p2 = data_in[2] ^ data_in[1] ^ data_in[0];

assign ham_out = {p0, p1, data_in[3], p2, data_in[2], data_in[1], data_in[0]};

endmodule

module main;

wire[3:0] data_in = 5;

wire[6:0] ham_out;

encoder en(data_in, ham_out);

initial begin

#10; //update every 10ns

$display("%b", ham_out); //print 3 parity bits + 4 data bits = 7 bits

end

endmodule

Note the positions of the parity bits and the data bits. [p0 p1 d3 p2 d2 d1 d0]

Input

There was a server you could connect via netcat. The server continuouly printed data like:

Captured: 1100101101010000000011001100100010000010101001111000011101000001110000110011110100011100110111111101000111100110011101101001111000011110110110010011001010110011011111010100101011011110000111000011100001001000000100110101010100000111000011010010011111001100010110010111001100010010110011011010010000110110100100010110011001000111110100011101011000100110000010110000111010110111010011111001000100010110000000000111001000000100101010101111001001100111111001001011011000110001111001001011011111110101110000110001111101010111001110000101001111001010001100110100100111001100010111010111110011110100101111110110000110001111110111111100001000011100001101001011111111110000110100001000011000010011001001110011100111010100111100110101101111001111010010001001010111000000101111111011000110000111111000111011111000011110100000001010101111010001100011111100001001010010001101001011000010111101110110110110110101001100111100100001010011011000010011101100011001100001

Captured: 1001100111010011111011001100100110001010100001111001001110001101101000010001110111011000111100001111000011101101000101110111101010110110100110011011001100100011011101000100101111111100011100000011000011100010001110100000010110000111011011010001011111111100110110000111011110010001111011010010111100010110100100010110011100101011110000111000011110100110000110101101011010111111110001011100101110000110000000000111101001010000101101110111001101000001110010110111101100110001111001000100101111110010110010000001011111000010000110011111000111101010100101111111100100011101010101100110010001000101111111111110000110001111111000001100001000111100000000001011111110010001110000011000011110110011101101010101010011011101011100110001000011000101000010100001100100010100001110010110110111001111011110011111111110011100110001001011111111100001001000010110100001011011101001000011010011111111111100110010010011010001110100000101110010011000001001110000000011110111

Analysing the data, we can see that:

- The length of the bit stream is 952 bits

- There are 136 blocks, each having 7 bits. Each block has 4 bits of data and 3 bits of parity.

- So, there are 68 characters of information in each bit stream, which is presumably our flag.

I captured a few seconds of output and saved it locally.

Hamming Code Algorithm.

- The input stream contains 4 bits of data and 3 bits of parity.

- Recalculate the parity using the 4 bits of data using the same calculation

- Say, the calculated parity bits were

cp0, cp1, and cp2 - Now, comparing the calculated parity bits to the transmitted parity bits results in the following scenarios

- Remember, we are considering only errors in one-bit per block only.

error in bit >>| p0 | p1 | d3 | p2 | d2 | d1 | d0 | no error

---------------+---------------------------------------------

cp0 matches p0 | no | yes| no | yes| no | yes| no | yes

cp1 matches p1 | yes| no | no | yes| yes| no | no | yes

cp2 matches p2 | yes| yes| yes| no | no | no | no | yes

modified from Code Golf - Correct errors using Hamming(7,4)

Implementation

- For each block of 7 bits, apply the algorithm above to find the index of the error (if any)

- If the data bit is in error, flip it. (We can handle only one error)

- Save the 4 bits from the block and correct the errors in the next block too.

- Convert the 8 bits from 2 blocks to a character. Add it to our potential flag.

- Doing this for a single bitstream, yields a character string like:

H L»ømm]w5Th_u2m][!ÎaÑ@sQ5 yp}_c4n_3x1ract¸ hS aami n Vg_4 3 Ó]f|¢^-

- That doesn’t look like the flag we want!

- However we have some readable segments of the flag there. So, logic suggests that we had more errors in the bitstream than what we could correct using the parity bits.

- Running the same logic on several more samples gives us results like:

H L»ømm]w5Th_u2m][!ÎaÑ@sQ5 yp}_c4n_3x1ract¸ hS aami n Vg_4 3 Ó]f|¢^-

HT ;8mmYwqlh_q0o3_ana=ys9EQ¹6e_j4ýf3x9ract 9h3\h0moÛm0ï7S0_:îj_6l¼:}

øTBÛ-mm_w1}` s c=_a`aÕxs1=Z~0 _c4n :r9¸áÃtÏ7hS øßmmkþ=_wo _9îº_eb 9}

...

So, we can deduce that while errors are randomly distributed, we are getting the flag being transmitted continuously in the bitstream.

The “correct” character in each position is determined by most frequently appearing character in that position across many samples.

Create a small program to count the frequency of every letter that appears in each position.

Running the error correction logic against the samples I had saved locally and selecting the most frequently appearing character yields the flag

HTB{hmm_w1th_s0m3_ana1ys15_y0u_c4n_3x7ract_7h3_h4mmin9_7_4_3nc_fl49}The complete code for the solution is here

References

Pedantry

In the writeup section after the CTF, I read an interesting comment that said it is more efficient to ignore the data if there are parity errors than to attempt to corrent the bits. I wanted to see if this was indeed the case. So, I set up an experiment with the sample data that I had.

The techniques I used were:

Ignore parity and just brute-force it: Since, we have an potentially unlimited messages, if we collect enough messages, we should have enough message fragments to give us the full flag. I saw that some teams indeed solved the puzzle this way.

Check the parity bits and accept the data bits only if the parity check passes. Else, discard the data bits. This was the scenario mentioned in the discord comment.

Check the parity bits and correct the bit errors as intended. The hypothesis is that this approach should be most efficient, as it maximizes the information in the messages.

I ran the same samples I had gathered against all the three algorithms. The results were not very surprising.

| Approach | # of samples |

|---|---|

| Ignore parity | 39 (still was one character off) |

| Check parity only | 28 |

| Check & correct | 18 |

So, it is efficient to take the effort and correct the bit errors, even if it does not eliminate all errors in the message.

Here is a relative comparison of the three techniques.

[X axis - # of samples, Y axis - # of errors from the expected flag]

Any of these techniques would work in the context of this challenge, as there were unlimited samples. The distinction would become relevant only when we have a limited set of samples.

Thank you for indulging in my silly pedantry.

Secret Code

Category: Hardware/Easy: (300 points)

Description

To gain access to the tomb containing the relic, you must find a way to open the door. While scanning the surrounding area for any unusual signals, you come across a device that appears to be a fusion of various alien technologies. However, the device is broken into two pieces and you are unable to see the secret code displayed on it. The device is transmitting a new character every second and you must decipher the transmitted signals in order to retrieve the code and gain entry to the tomb.

Files

Archive: hw_secret_code.zip

Length Name

--------- ----

0 broken_board/

592 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-Edge_Cuts.gbr

1173 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-F_Mask.gbr

2670 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-job.gbrjob

788 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-F_Paste.gbr

8722 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-F_Cu.gbr

1990 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-B_Silkscreen.gbr

474 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-B_Paste.gbr

329373 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-F_Silkscreen.gbr

2869 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-B_Cu.gbr

859 broken_board/RA_CA_2023_6-B_Mask.gbr

96157 hw_secret_codes.sal

--------- -------

445667 12 files

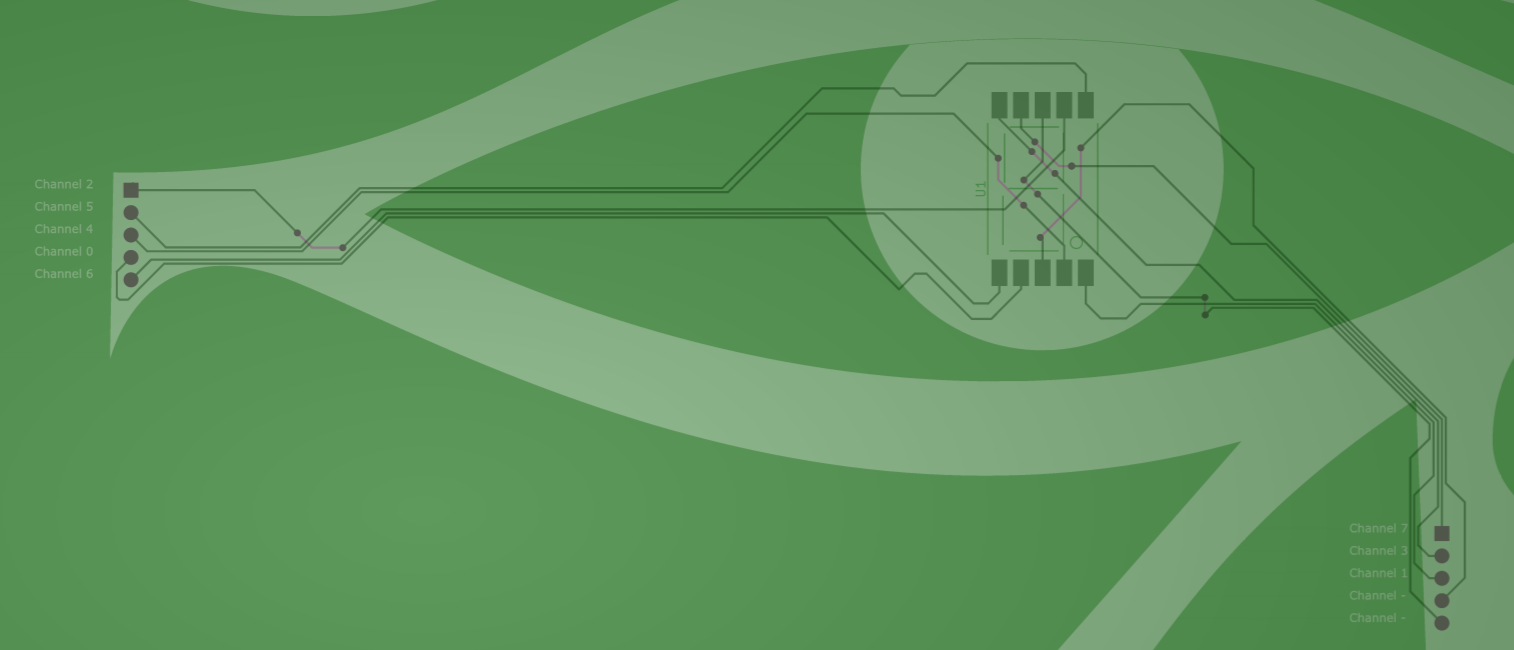

PCB analysis

Upload the zip file to a site like PCBWay to view the Gerber files. Tip: tweak the colors for the different layers to improve visibility

The most important information is from this section of the PCB. Note the magenta colored links are on the bottom side of the PCB, acting as cross-overs.

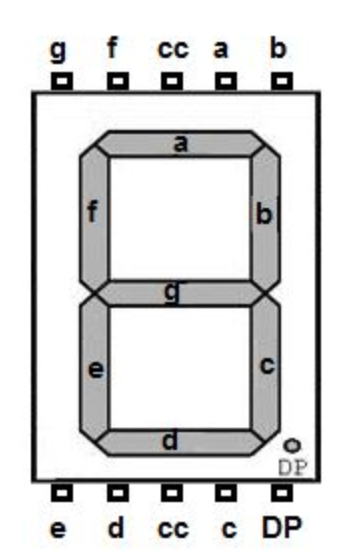

Tracing the connections to the typical 7-segment LED display, which is silkscreened on the PCB, gives us the following signal paths

| Channel | Segment |

|---|---|

| 0 | d |

| 1 | DP (dot) |

| 2 | a |

| 3 | g |

| 4 | c |

| 5 | b |

| 6 | e |

| 7 | f |

Signals

Also included in the zip file is the Saleae Logic 2 file called hw_secret_codes.sal

Using File -> Export Data -> CSV lets us have the data in a CSV file. Looking at the channel 1 (the dot on the display), it pulses approximately once a second. So, we cue off that signal and read the values when channel #1 is high (i.e equal to 1).

Time [s],Channel 0,Channel 1,Channel 2,Channel 3,Channel 4,Channel 5,Channel 6,Channel 7

0.000000000,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0

0.695667880,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0

0.695672280,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,1

0.695680200,0,0,0,1,0,1,0,1

0.695691400,0,0,0,1,1,1,0,1 |_|

0.695695040,0,1,0,1,1,1,0,1 <=== reading #1 |.

1.696727760,0,0,0,1,1,1,0,1

1.897122440,0,0,1,1,1,1,0,1

1.897129960,0,0,1,1,1,1,1,1 _

1.897133720,1,0,1,1,1,1,1,1 |_|

1.897141520,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1 <=== reading #2 |_|.

<snip>

The CSV data is as depicted above. Ignoring the timestamp and all entries where channel #1 is 0, leaves us only the good readings. In the snippet shown, there are two valid readings. If we map the channel values to the segments as described before, we can see that the segments spell 4 and 8 as two consecutive readings. 0x48 is the ascii value of the letter H.

Code

Instead of building an elaborate lookup table, I decided to just print the character on the LED display to the screen and transcribe it over to Cyberchef.

def print_digit(sig):

CHARS = "_ __|||||"

DISPLAY = [

[' ',' ',' '],

[' ',' ',' '],

[' ',' ',' '],

]

POSITIONS = [7,2,1,4,8,5,6,3]

for i,c in enumerate(sig):

if (c):

p = POSITIONS[i]

DISPLAY[p//3][p%3] = CHARS[i]

D = []

for l in DISPLAY:

D.append(''.join(l))

return D

# returns 3 strings corresponding to the three lines of the display.

Flag

Printing the LED display for the entire set of signals (where channel #1 is 1), gives us the following output:

Transcribing the hex values displayed 4854427b70307733325f63306d33355f6632306d5f77313768316e4021237d into ASCII using CyberChef yields the flag : HTB{p0w32_c0m35_f20m_w17h1n@!#}

Reflection

This was a very enjoyable challenge. It brought back memories of my early experiments of tinkering with electronic circuits.